2024 in Review

One must live a year facing forwards, but one can only understand a year looking backwards...

It is the end. More precisely, it is the end of 2024. Like all internet blowhards, I have assembled a list below of my myriad efforts in both consumption and production. But since I consume and produce literature, words, art, and things, I can comfort myself with the thought that at least this is contributing to the betterment of society somehow.

2024 was the year of the slop. AI generated nonsense across every single idea that can also live in your phone: instagram, twitter, spotify, facebook, tik tok.

So here’s grist for the slop mill: my list of all the shit I wrote this year, the best books I read this year, and some of my favorite articles from the year. Eat your heart out, ChatGPT.

Shit I Wrote:

This year I wrote 12 pieces. That’s 1 a month. A great majority were published here, on substack, although not always on my substack.

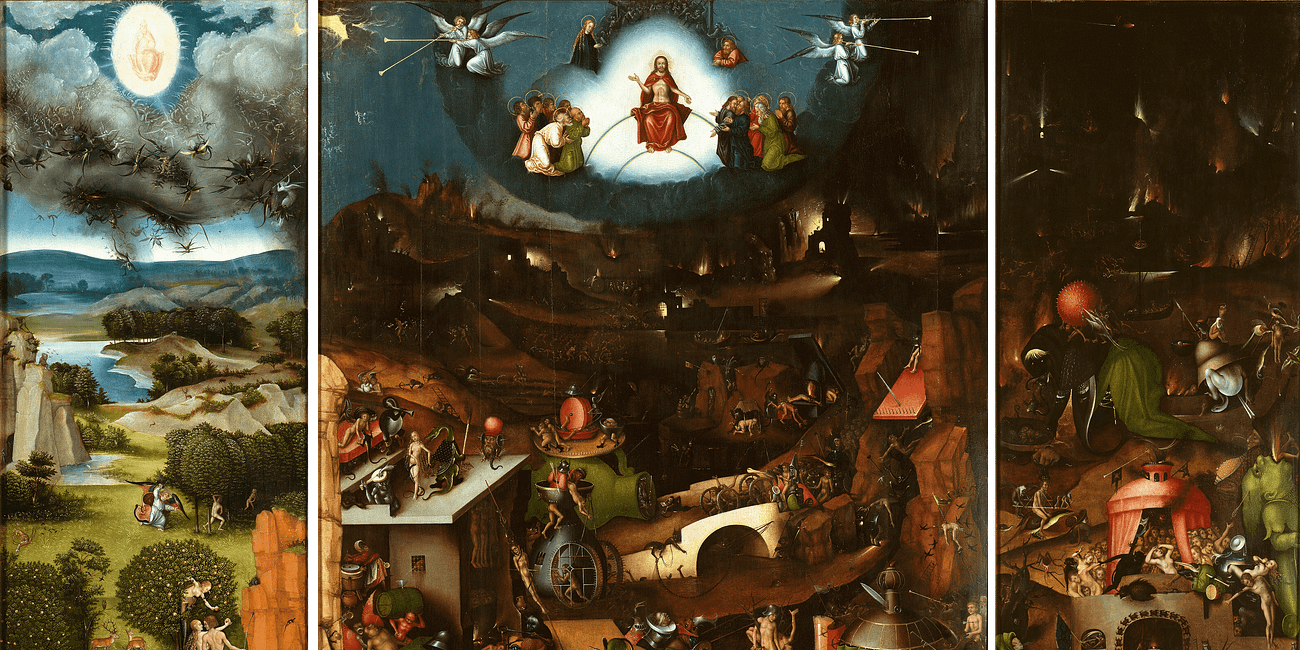

In a year marked by the horror of the return of genocide as a feature of global politics, I started out in January by writing about one of the great post-Holocaust writers: Aleksander Tisma. Tisma’s Novi Sad triology is one of the most incredible and bleakest things I have ever read, a triptych on the way guilt works and moves throughout society. If you haven’t read these books I really recommend you do. The will annihilate you. And despite all of Tisma’s grimness, I argue there is indeed some principle of hope at work in his novels.

The Use of Principles: On Aleksandar Tišma’s Novi Sad Trilogy

·Bleak is the most common word to describe the writings of Aleksandar Tišma. His Novi Sad trilogy – The Book of Blam (1972), The Use of Man (1980), Kapo (1987) – is considered, ‘hopeless’, ‘relentless’, ‘without respite’. It takes as its subject the Holocaust, and more importantly the afterlife of such an event. Tišma’s clever twist, what sets his novels…

At the end of January, I finally finished Ulysses. I wrote about it for the

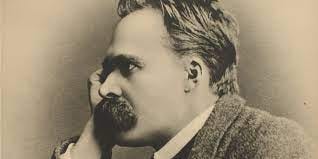

. Despite the book’s difficulty, there is a certain equality and communism to it. In its subject matter, of course, but in its prose as well.In February there was an awful lot of discourse about Friedrich Nietzsche. Daniel Tutt published his book “How to Read like a Parasite,” exposing the truth of a deeply fascist Nietzsche completely incompatible with the left that had been exposed before him by Dominic Losurdo, and before him by Richard Wolin AND before him by one George Lukacs. This was starting to all feel kind of tedious, so I wrote about why leftists might find Nietzsche compelling, without devolving into Deleuzianism.

Nietzsche and Us

·One can characterise modernity as the realm of the relentlessly new. But it is also the realm of repetition. We are in an eternal interregnum. In the 1930s Antonio Gramsci famously declares that “the old is dying and the new cannot be born.” Yet it appears we have been stuck in this moment ever since, and the eternal recurrence of this quote indicates t…

In March, I wrote about Gerald Murnane’s Inland. The book was released in the US by And Other Stories Press. Inland is a singular novel, vexing and strange, equal parts letter, monologue and reverie. Murnane’s mind is a strange place, but I spent much of the review pushing back against the idea that he is as weird and idiosyncratic as people think. You can read it here: https://www.ronslate.com/on-inland-a-novel-by-gerald-murnane/

In April I wrote about Andrey Platonov’s epic masterpiece Chevengur. A 600 page love letter to peasants, the revolution, the commune, and utopia, it was without a doubt one of the best books I read this year. And its heavy allusions to Don Quixote could not but help remind me of another figure who believed it takes a little bit of madness to make the world better: the Spanish philosopher Miguel De Unamuno.

How to Read Platonov like a Communist

·August 1929. Andrey Platonov, writer and engineer, has penned a letter to Maxim Gorky. He is unable to publish his latest novel, Chevengur, in its entirety. He appeals to the revolution’s literary darling for help. Gorky’s reply praises Platonov for being a master of “a very distinct language.” However, Platonov’s anarchist tendencies are too evident. W…

In May, I wrote about one of my literary heroes, Elias Canetti. This year, New Directions published his book, “The Book Against Death”, a collection of aphorisms and reflections on death and literature. Canetti said he “accepted no death”, and found, in the realm of writing, the tools to resist oblivion. It is a sentimental sentiment, but one I agree with dearily, as my closing remarks in this piece indicate. https://themillions.com/2024/05/elias-canetti-words-against-death.html

In June, I published the first of my three ‘summer essays’ at The Hobbyhorse. The first was on Franz Kafka and our relentless drive to publish all his notes, letters, diaries, office emails (not really a joke) and maybe soon his tax returns (hopefully a joke)? I term these objects “Hypographs". I object to this desire for the archive immensely and make my case in this piece.

In July my second summer piece for the Hobbyhorse dropped: Saint Bovary. In it I discussed Gustave Flaubert’s magisterial Madam Bovary and the limits of understanding Flaubert as a realist. Indeed he was much more of a mystic, believing in the divine powers of art. How and why, then, did he write such a grim and ‘realistic’ novel? Perhaps the answer has something to do with the limits of realism itself.

You might think that in August my final summer piece with the Hobbyhorse came out. No. Instead I wrote another piece at the substack, exploring Michel Foucault’s approach to inquiry, his theory (or lack thereof) of the state, and his vision of radical politics. The inspiration for this piece stems from a lecture he gave in Toyko in 1978, where he outline his theory of the relationship between political philosophy and the state.

A Certain Method of Inquiry

·In Tokyo on April 2nd, 1978, Michel Foucault gave a lecture entitled “the Analytic Philosophy of Power.” In it, he makes several remarkable comments about his own work and how he conceives of it. Crucially, Foucault does three things that I think are clarifying for understanding how his work can be situated between philosophy and politics. These are: 1)…

Things returned to normal in September, with the final installment of my summer essay series for the Hobbyhorse. There I wrote about Yukio Mishima and the empty core of his sometimes stunning novels. What exactly is going on with his world view? Why did he go out so spectularly, and what are we to make of his aesthetic principles? It all revolves around attempting to answer a simple question: Did Mishima Die Happy?

In October, my review of Yoko Tawada’s Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel was published by the flawless folks over at The Cleveland Review of Books. These heros, veritable legends, were so good to let me go long - over 4,000 words - on yes Tawada but also the intricacies of Paul Celan. You can read it here: https://www.clereviewofbooks.com/writing/yokotawada-paulcelanandthetranstibetanangel

In November I ate a big bird. I also had a short and weird text published over at

. This piece was a 500 word essay where every word had to contain the letter ‘e’, a reverse lipogram. I wrote on Emerence and Ennemonde, two figures of European peasant life in European literature. Lots of ‘E’s in that sentence you see. https://minorliteratures.com/2024/11/26/emerence-et-ennemonde-depicting-european-peasant-life-duncan-stuart/

Shit I Read (Books edition):

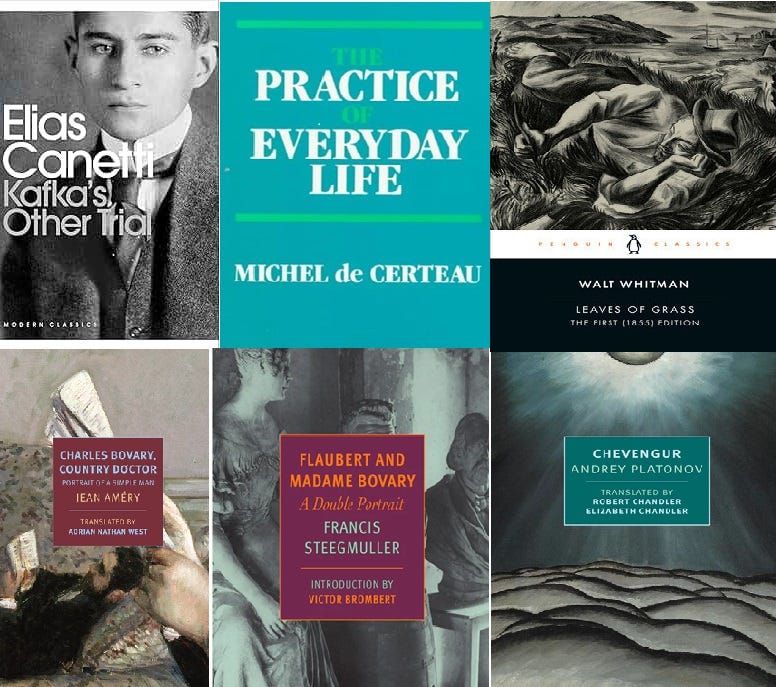

I read 45 books this year. Some people read 100, some people read like 6. My six favorite (6 because it makes a nice graphic) were:

1) Chevengur - Andrey Platonov

- A wonderful, surreal book, replete with some of the strangest and yet most compelling characters in literature. A touch of Pilynak, a touch of Cervantes, a touch of revolution.

2) Kafka’s Other Trial - Elias Canetti

- One of the best books on Kafka, and one of the only books that takes seriously the issue of us plundering his letters constantly, as I wrote about in my essay on Kafka. Canetti shows how Kafka’s letters to Felice Bauer became part of his work, especially his novel The Trial. But he reverse it the usual claims in Kafka scholarship: it is not the letters that help us understand the novel, but the novel that helps understand the letters.

3) Charles Bovary, a Country Doctor - Jean Amery

- A stunning little book, that attempts to redeem literature’s greatest cuckold. It is Amery’s insight to say that after the holocaust, perhaps we should reevaluate our disdain for Dr. Bovary.

4) Flaubert and Madame Bovary - Francis Steegmuller

- A wonderful biography of Flaubert’s life up to and including the writing of Madame Bovary. Part of its excellence is the middle section, which solely comprises letters of Flaubert, his mother and his friend Max Du Camp during a trip to “the Orient” (North Africa and the Levant).

5) Leaves of Grass - Walt Whitman

- What is there to say? Whitman’s heroic, exuberant poetry takes seriously the idea of an exhortation to all beings and all modes of life. One of the most successful attempts in literature, nay ever, to think everything and be everything.

6) The Practice of Everyday Life - Michel de Certeau

- You might think de Certeau is a silly French postmodernist. Actually he is a philosopher in the purest sense, keen to know everything there is to know about thought. His work restores the intellectuality and power of the ordinary through an incredibly learned and detailed study of language, life and philosophy. Plus he is a stunningly good writer.

Or, if you prefer pictures:

Nice. Please ignore the stretched pixels.

Shit I Read (Essays, Articles, and Propaganda):

I read a lot of essays and articles and so on in the course of the year, and there were a few (actually quite a few) that really stood out to me. Of course, in talking about cultural criticism published this year, one must start with the topic front and center of our discourse: the genocide in Gaza. It didn’t come out this year, but Raz Segal’s essay “A Textbook Case of Genocide” written a mere week after the events of October 7th, 2023, has been vindicated by events and the recent Amnesty International Report, declaring Israel’s actions in Gaza a genocide. I think it was there for all who know the history of Israeli miltary activity to see this outcome. Those who joined on the streets to protest what was happening in Gaza knew this too. Those who dismissed activists and writers and unwaveringly supported Israel are now party to the crime against humanity.

So two of the best articles I read this year concerned this. The first was Pankaj Mishra’s “The Shoah after Gaza.” This piece is Mishra attempting to think through the double moral conjuncture of The Shoah and the genocide in Gaza. The Shoah produces both the immediate conditions for the state of Israel and is also the cover for Israel’s doctrine of absolute force. In a painstaking analysis of some of the great post-Shoah writers - Primo Levi, Jean Amery - Mishra finds that the call to conscience in these writers can and does apply to our present moment.

The second piece was Erik Baker’s “Burnt Offerings” in n+1. n+1, like Jewish Currents, was consistently on the right side of the issue, publishing careful, detailed analyses of the situation in Gaza. Baker’s piece draws together the history of incendiary weapons with the protest tactic of self-immolation. Aaron Bushnell, who set himself on fire to protest the genocide in Gaza, is but one part of this dual history. Baker is clear-sighted about all of this, and writes in one striking passage the following:

the purpose of lighting yourself on fire is not to encourage other people to light themselves on fire. It is to scream to the world that you could find no alternative, and in that respect it is a challenge to the rest of us to prove with our own freedom that there are other ways to meaningfully resist a society whose cruelty has become intolerable.

The other articles I read and loved this year were much less grim. Yet some of them were not so far from this topic. In Helen Rouner’s “Dust to Dust” - published in Commonweal Magazine - she relates the power of Auden’s poetry to the long shadow atrocity casts on human life.

Likewise, a post at a substack called

, on Jean-Paul Sartre’s magisterial biography of Jean Genet, offers a picture of writing as a way out of despair, of freedom being the only way we can account for the totality of the person. The world produces atrocities, and writing can act somewhat against this. Although the sentiment is glib and will not bring back the dead, writing is not a pure act of futility. Something like this emerges in Sartre’s treatment of Genet, and Five (as we will call him) is right to highlight it.Although it’s not mentioned by Five, lurking in the background here too is the fact of Genet’s book on Palestine, Prisoner of Love, as well as Sartre’s own interest and defense of anti-colonial movements.

In addition to this, there were several reviews I thought were really good. Two by Alina Stefanescu really stood out. The first was her magesterial review of Robert Glück’s “About Ed” in the Cleveland Review of Books. That was in Feburary. Then, in October, Stefanescu wrote another fantastic piece on Annie Ernaux’s “The Use of Photography” for the LARB. One thing I appreciate in both these works is the careful and rather delicate discussion of desire. There is, I think, a certain tedious hedonism to our age, but desire is not a reed to be grasped and pulled out from the river, but an eel that slips back into basin after your first lunge.

I loved Ryan Ruby’s review of Rachel Kushner’s new book Creation Lake. In particular it offers a nice example of how to write about politics, the novel and the politics of the novel, all brought together in this antepenultimate paragraph:

We have just seen, in the case of Creation Lake, how Kushner’s choice of narrative perspective and character have the effect of disaggregating a collective into its component individuals and reducing political convictions to personal interests. We should add that these are political outcomes baked in to the literary form of their representation, not into reality itself. The charge that Sadie levels at Lucien and that Bruno levels at Pascal—that their respective attachments to ’60s- and ’70s-era figures like Godard and Debord are forms of nostalgia and romanticism—could also be leveled at Creation Lake, which reads like a literary-fiction adaptation of the aforementioned Jean-Patrick Manchette, whose Debord-influenced crime thrillers about female assassins, anarchist collectives, undercover cops, and political demonstrators were written half a century ago, in the early years of the neoliberal counterrevolution. In other words, Creation Lake may describe a period of political restorationism, but is itself an instance of aesthetic restorationism. As such, it not only formally mirrors the political impasses of its own time, it reproduces them. It may be easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but it is no less difficult, it seems, to imagine a new form for the novel. Perhaps these two difficulties are not unrelated.

In The Baffler, Bailey Trela wrote a wonderful review of Cristina Campo’s The Unforgivable. More than anything else this was just a simply wonderful piece of writing from Trela, who brings his winding threads and dynamic prose to a really superb denounment:

A face, a pupil, a motionless point—I’m tempted to add another nodal image to this list: a nut. Nuts crop up everywhere in The Unforgivable, spotting the loam of Campo’s prose like so much windfall. It’s no coincidence that her sole autobiographical essay, a roseate evocation of childhood that cloaks her experiences in the rhythms and motifs of fairy tales, is titled “The Golden Nut.” In at least one sense, the nut is a symbol, for Campo, of secrecy—perfectly sealed, perfectly whole, like the sayings of the Desert Fathers, which “were almost always very hard, uncrackable nuts, to be carried around for life and crushed between the teeth, as in fairy tales, in the moment of gravest danger.” Inside there is flesh, folded and crimped—life’s originary point, the mystery of sense.

In the Sydney Review of Books, I really enjoyed Louis Klee’s review of “Barron Field in New South Wales: The Poetics of Terra Nullis”. This book, by Justin Clemens and Thomas H. Ford is a investigation of one of Australia’s first judges Barron Field. Field sets out to write romantic poetry about Australia in Australia and in turn tied the history of Australian poetics to the displacement and slaughter of its indigenious population:

There is no need for captivity and civilising, Field’s poem implies. This is because he has assumed – in an early and oblique version of what would later become one of the most iniquitous lies of Australian colonisation – that First Nations people will die out ‘in the eye of Nature’, which is to say, ‘inevitably’. Australia, for Field, was not conquered, but taken under the fiction that it was uninhabited, and in the poem this fiction sits alongside another, kindred fiction: that settlers are not responsible for the ‘decay or extermination’ of First Nations because that will happen ‘in the eye of Nature’, as a matter of course.

That Field chose to deliver the genocidal meaning of terra nullius before the new governor of the colony in a reworked fragment of Romantic verse casts a painful shadow over Australian poetry.

Finally, I want to highlight J. Arthur Boyle’s superb essay from the start of the year, “The Artist’s Self-Interest: On Capitalist Fiction” published in The Cleveland Review of Books. A review of Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction, Boyle moves through the difficulties of fiction, publishing and capitalism in heated prose that expands and contracts, that pulses and writhes as it forms an impassioned sermon against the vissicitudes of congelmerate publishing. Our literary lives, our artistic lives, could be better and Boyle’s blood grows hot as he relays Sinykin’s account of what stands between us and a better, more creative world. Published all the way back in January, it was a wonderful essay that heralded what was, in fact, a really superb year for criticism and fiction. So let us end with Boyle’s final words, an ode to art and writing and all things good and beautiful, against the tryanny of value:

Art is the best language humanity has for understanding where, and what, humanity is. That is why art is beautiful to us—it creates and affirms the many meanings we have for ourselves. Capital, as a societally organizing force, does not have a way to value this function, because the value exists outside of utility. Because capital cannot assign a value, it treats this function as irrelevant, thereby rendering it irrelevant. In this case, no one could claim to love art and simultaneously tolerate the dominance of capital, as they inherently contradict each other. And if you don’t love art, how could I be particularly interested in yours?

See you next year, suckers.