2025 in Review

I wrote, I read, I wrote about what I read...

It is the end of the year. No really, there is less than a week left in 2025. Most end of year lists appear at the beginning of December, leaving 3 or 4 weeks of the year untouched by our benevolent tastemakers and/or minor bloggers.

This disadvantages those whose work appears in this desolate December; these writings are condemned to oblivion. December: the month of silence, of holy nights.

Personally, this irks me. This year I had 7 pieces come out (pretty good for a guy with a full-time job) and 5 of them came out in November and December (I had a heroic run wherein these 5 pieces were all published in the space of four weeks).

It also causes problems for the workhorse magazines and publications, which don’t seem to take time off. This year saw the rise of Ross Barkan and Lou Bahet’s The Metropolitan Review, which seems to be able to publish something almost every day. That’s dedication – and where do all these writers come from? – but I don’t think any of their December pieces will make an end-of-year list this year or next. Except for mine, of course, because I am about to tell you about all the things I published this year, including my essay for The Metropolitan Review, which came out on December 11th.

What awaits below, however, is not just a self-indulgent list of my publications. Below you will also find my favourite reads of the year, including both books and articles, and perhaps a reflection or two on 2025. Sure, it was the first year of the second Trump presidency (three more years), but more importantly my first full year of gainful employment. I’m amazed I had time to read or write at all…

Shit I Wrote:

1. The Twice Examined Life – On Paul Valery (Exit Only)

After am absurdly productive 2024, wherein I wrote 12 essays in 12 months, this year things began at a halt. I didn’t get anything off until April, when I managed a brief review of Paul Valery’s Monsieur Teste, his only work of fiction, an odd little book about a philosopher everyone loves and praises but remains ill at ease. This was a good chance to use substack’s image insertion feature to not quote poems but present them. In discussions of poets like Mallarme actually seeing the poem really aids the analysis.

Monsieur Teste invokes the tension between philosophy and poetry, the old question of how the artist relates to the truth. Depends on who you ask, but make sure you ask someone who knows the history of poetry, or you will get an awfully annoying answer. For Valery there is no easy distinction; man carries both truth and poetry in his heart.

2. Mediation without History – On Anna Kornbluh’s Immediacy (Hobbyhorse)

Several months passed. Then in August, I published an essay on Anna Kornbluh’s Immediacy over at the Hobbyhorse. Yes, the book had been out for a while, and yes, I did think it was funny to publish an essay on a book called immediacy so late, but also I found Kornbluh’s analysis to be deeply misguided. You can read the piece in full yourself, but my basic position is this: American scholars love doing a little bit where they’re like “the French have abandoned Marx and it is up to us, Americans (?!?!) to restore Marxism to its true and mostly Hegelian roots.” Somehow our science of history, our historical materialism, is losing that historic edge. Look at the process a little more and you’ll see several historic reasons that inspire the shift in analysis and the emergence of post-Marxism in Europe. But history has never been Americans strong suit, eh?

3. Marxism as Egalitarian Ethos (Negation Magazine)

Over at Negation Magazine, I wrote 10,000 words about Marxism, Everyday Resistance and the Rarity of Politics Thesis. All capitalized because they are all big name IDEAS. It’s long but I think it is good and you should read it. Of course I do, I wrote it. Again, in short: from Marxism one derives both the idea of everyday politics and resistance (via Henri Lefebvre) and also something called the rarity of politics thesis. You can find this idea somewhat in Lenin and even CLR James, but it appears strongly in French Marxism via Badiou, Ranciere and Lazarus. All it states is that politics, politics that effects some major change, is rare. These ideas make opposite claims – in everyday life politics occurs all the time; in the rarity of politics thesis it almost never occurs! Are the views reconcilable, how do they relate to the same tradition, what are we to make of this gap? And what does it tell us about people’s capacity?

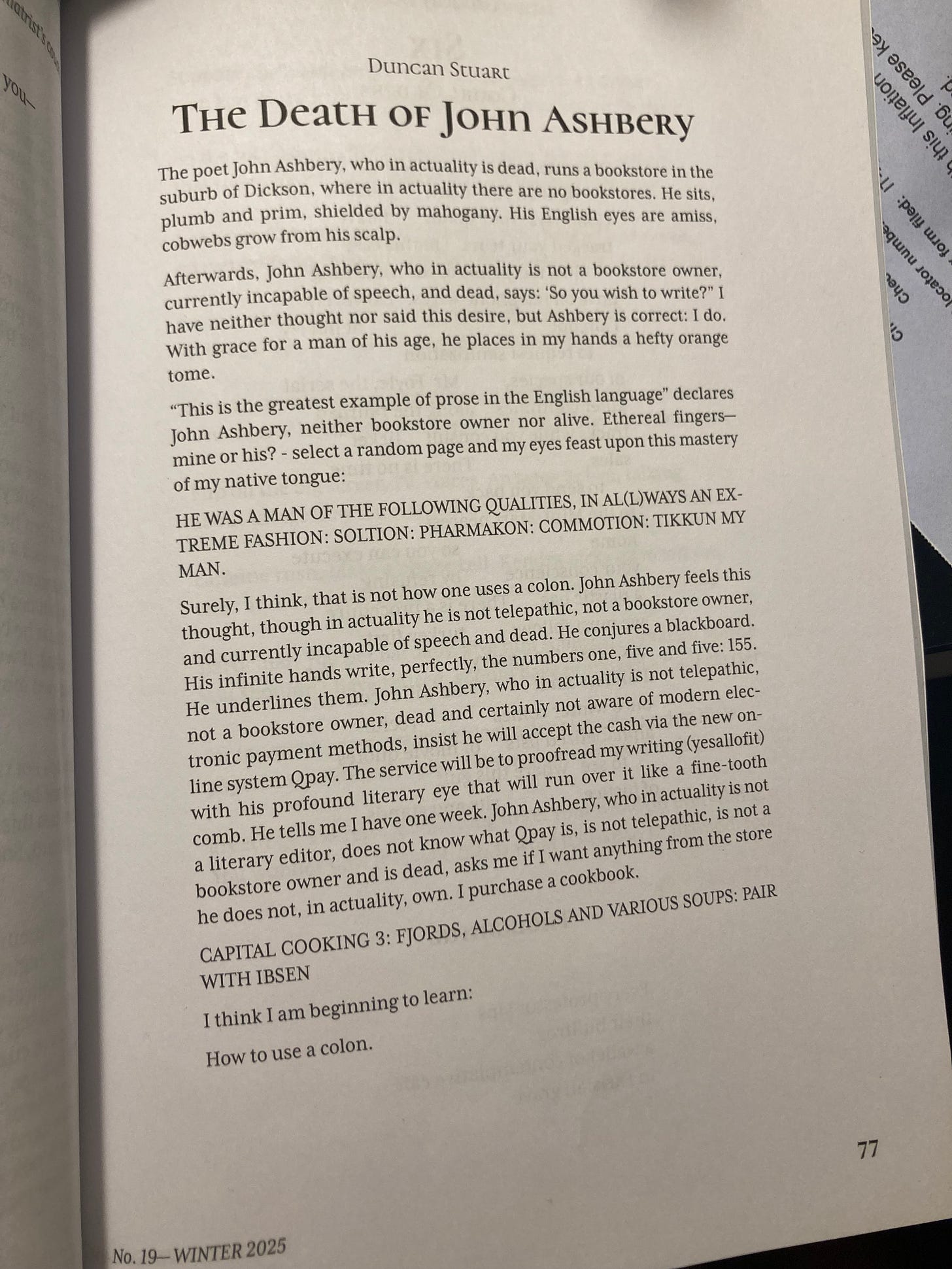

4. The Death of John Ashberry (The Exacting Clam)

Once I had a dream. I dreamt of John Ashberry. Awaking in a cold sweat I rushed to my laptop and wrote down this dream in a lush and vibrant prose poem. Half a decade later, it still having been the only remotely good poem I ever wrote, I sent it to the Dada issue of the Exacting Clam. They obliged and published my insanity. Image below so you can read it and enjoy it.

5. The Pits of Inspiration (A Common Well Journal)

I love my friend Hank. And my friend Hank has restarted his old journal, A Common Well (not to be confused with Commonweal, the left wing Christian magazine). As part of the revamped and reamped journal, Hank is publishing little missives on the website, writers on writing. I contributed to the first round of these. In my short piece I argue that inspiration is not the act of creating something – the house of fiction, if you want – but is more like searching in a pit for a half remembered idea. In 1500 words I somehow invoke God, Henry James, Gerald Murnane, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Andrey Platonov. I removed, from earlier drafts, mentions of Giorgio Agamben and Thomas Aquinas.

6. On the 50th Anniversary of Hannah Arendt’s Death (Exit Only)

On December 4th, 1975 Hannah Arendt died. On December 4th, 2025 it marked 50 years of Arendt being dead. I took the chance to revisit some of the dumber aspects of the “Is it fascism yet” debate that emerged during Trump’s first term. Samuel Moyn and Corey Robyn had I think this silly idea that there is this thing called fascism with certain characteristics, and you hold up what is happening and ask if it matches the criteria. This all sounds rational, and they benefited from the aesthetics of reasonableness. However, this kind of missed the point of all those people invoking Arendt back in 2016. See the whole point of Arendt’s analysis of fascism is that something unforeseen emerged, and that politics requires a certain vigilance in age where oue old modes of thinking and moralizing have been disrupted. The price of this vigilance and this awareness of the new as fundamental to politics is a certain degree of what might appear to be hysteria. I felt a missed opportunity here to invoked Junger’s lovely novel On the Marble Cliffs, which I wrote about in 2023, a book about being sealed in your ivory tower and waiting until it is too late to act because you are a reasonable man of science and weigh all the evidence equally.

7. The Miraculous and Miserable City (Metropolitan Review)

This year marked 100 years of one of my favourite novels: John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer. I took the chance to write about it for the Metropolitan Review, and used this chance to also write about the intertwined history of urbanism and literary modernism. I chart the evolution of these two not through writers like Charles Baudelaire or Charles Dickens (a history that is as true as it is well trodden) but across the evolving work of three poets whose work is neglected these days: James Thomson, Emile Verhaeren and Mario de Andrade. Their work charts an evolving literary sensibility that tries to increasingly capture modern urban life. Along the way I discuss Robert Walser, Thomas Mann and James Joyce, all before finally getting to John Dos Passos’ masterpiece. I’m happy with this one, but unfortunately it lacks a certain juice: I didn’t pull anywhere near the hundreds or sometimes thousands of likes the Metropolitan Review sometimes gets on their articles. Never mind quantity versus quality, sometimes quantity transforms into quality. Or vice versa. Should have written about the male loneliness epidemic instead. Anyway, give it a read; it has been described as “good overall.”

Shit I Read:

Whole Ass Books I Read:

I have made reading books my whole personality. I care about nothing else. I don’t listen to music. I don’t know what a Pokemon or an Elden Lord is. When I talk to other people I look at my feet. I can’t name any sports teams. Luckily I am really good at this fundamental skill everyone use to learn in elementary school.

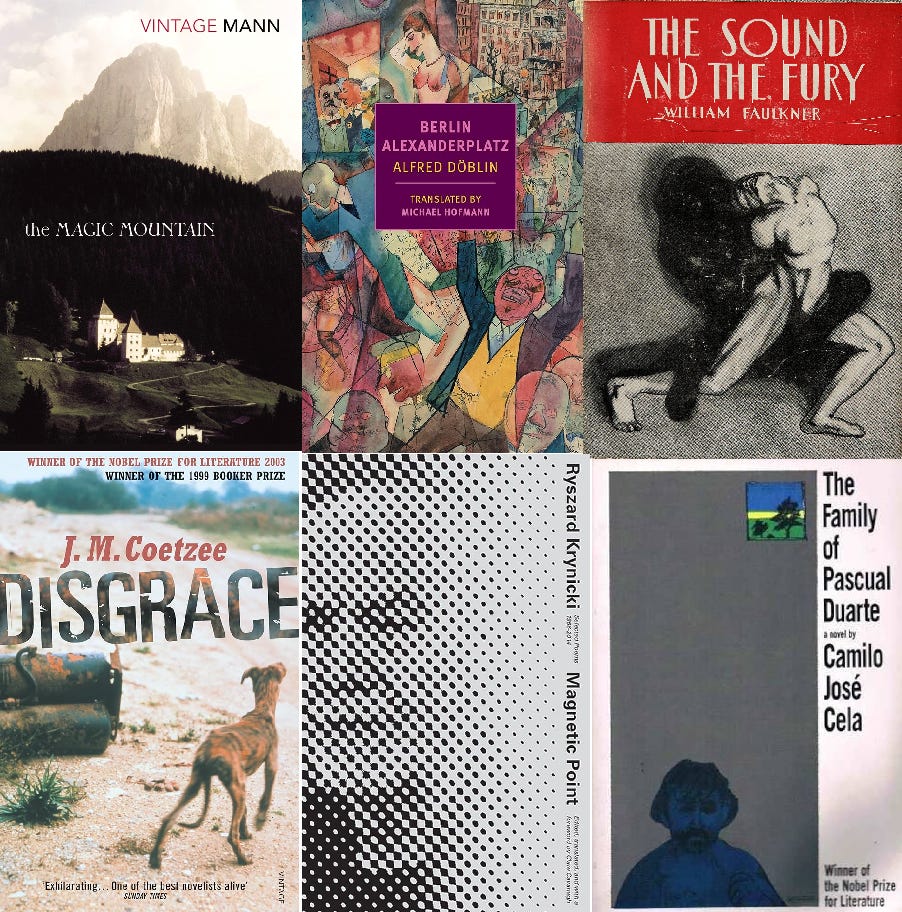

I read like 36 books this year (not bad for a guy with a full-time job) but some of them were like really long. Some people read no books in a year. Some people read 200. Those people are lying to you. Anyway, here are my six favourites, because six makes a nice graphic.

1. The Magic Mountain – Thomas Mann

I read the magnificent magisterial The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann mainly amongst my group of mates. I.e. I was in a reading group. I was the last to finish the book, early this year (we began November 2024). It really is fantastic, although I do admit you have to get into it. This is not a quick Sunday afternoon read. The book has its own temporality, as does life in the sanatorium where our hero, Hans Castrop, goes to visit and ends up staying. A beautiful allegory for European life pre WWI, a stunning meditation on the concept of wellness and living, and a lovely book about family (yes I’m being serious). I have never read a book so long (700 pages!) where I felt the length was so justified, every page and digression worth it. Banger. Must Read. 10/10. Five Michelin Stars.

2. Berlin Alexanderplatz – Alfred Doblin

This one has been on my reading list ever since, in my first year of university, I pulled a copy of Kathleen L. Komar’s Chaos and Pattern: Multilinear Novels by Dos Passos, Doblin, Faulkner and Koeppen off the library shelves and read it instead of doing my physics homework. That monograph analysed Manhattan Transfer, Berlin Alexanderplatz, As I Lay Dying and Pigeons on the Grass. That was over a decade ago, and I only have the Koeppen (Pigeons on the Grass) left to read. Anyway, point is I’ve being meaning to read this one for a long, long time. It is stupendous. Yes, it’s confusing, yes it’s chaotic, yes it’s upsetting. It is a wonderful novel about the world’s biggest moron who you can’t help but feel bad for (yes yes he is a violent misogynist, have you guys ever read a book called Lolita?). A masterpiece of humanist, socialist (yes!) and modernist writing, black and grey and bleak and hilarious.

One time, whilst in a bar, I spotted a lonely hipster reading this book. I asked him how it was going, he said “I’m not sure it’s for me.” I encouraged him to keep going, and if you pick this up and struggle I offer you the same advice: more courage!

Also this year I read one (1) Alfred Doblin short story called The Sailboat Ride and it was the best thing I’ve ever read.

3. The Sound and the Fury – William Faulkner

I have owned my copy of The Sound and the Fury for a decade. In a good example of the wisdom of the principle ot never get rid of a book, when I finally did read it I loved it. A stunning masterpiece, deeply modernist, deeply experimental and deeply humane. Indeed I would go so far as to say for Faulkner the humanism and the experimental modernism are inseparable; all thought can be rendered. People say Faulkner is about evil, but Faulkner is about alterity. I also read As I Lay Dying around the same time but The Sound and the Fury is without a doubt the superior novel.

4. Disgrace – J.M. Coetzee

He might be the best. Coetzee, I mean. Disgrace is so good. From the beginning there is just an all encompassing atmosphere of disaster. Everything, even that scene, unfolds in slow motion. Lurid David Lurie is such a great depiction of an educated middle-class shithead, and the intractability of his whole situation(s) is made so palpable. The final scene, where he ascends the hill and looks over the countryside is a really wonderful moment. In a sense nothing happens, but here Coetzee releases all the tension that the whole book has held. He places us, the readers, back on the shelf, just as we will do with his book when we close it. Also contains, as always, my absolute favourite Coetzee motif: old people having uncomfortable sex.

5. Magnetic Point – Ryszard Krynicki

Magnetic Point is a collection of poems from across the oeuvre of polish poet Ryszard Krynicki. I came across it when my friend Bailey left his Paris Review tote bag behind at a party. I started reading the books in his bag, which included Magnetic Point. I did return his bag to him, and got myself a copy of Magnetic Point, which I love. Krynicki’s poetry is a difficult but compelling, and reminds me a little of Paul Celan. While the holocaust hangs over Krynicki’s work – he was born in a Nazi labour camp in Austria in 1943 – it is the oppression of communist Poland that provides the friction that gives his work its impetus. In “The World Still Exists” he speaks of proceeding along the “street’s ultraleftist side”. He is a poet I have been looking for, and one whom only by chance did I find.

6. The Family of Pascual Duarte - Camilo Jose Cela

Picture this: Albert Camus’ The Stranger but it didn’t suck shit. The Stranger is alright, but I always felt, even has a rosy cheeked fifteen year old, that our amoral indifferent Meursault kind of does give a shit. Not so for Pascual Duarte, a complete and utter bastard. Pascual is our narrator and oppose to Meursault’s feigned indifference bordering on confusion (ah no the sun was bright now I killed a man) Pascual is direct, intentional and indifferent. Meursault cowers in the corner and this already suggests a conscious. Pascual can’t wait to kill those motherfuckers who put their hands on his sister. Only he is allowed to do that. Cela’s prose style, at least in the translation I read, is superb and the book is short and shocking. As far I as can tell Cela was somewhat of bastard himself, so no surprise he wrote such a good one.

Whole Ass Articles I Read:

The first article I read this year that I really loved was Aziz Rana’s Constitutional Collapse in The New Left Review. It’s a really wonderful essay, and make clear that all this talk of constitutional crisis has a long history. There were always weaknesses in the system, but we had to get here. This question – how did we get here? – Rana explicitly asks. The Cold War helped bring disparate elements of the American political spectrum together and kept more extreme racist positions out of play. Yes you wanted to be an anti-communist American capitalist, but you didn’t want to be a right wing nut job. If you had unsavoury views about non-whites in America, these had to be tampered by the constitution; ‘they’ were at least entitled to their civil liberties. The end of the cold war allowed those fringe position to come back in:

Yet once the USSR was gone, we therefore witnessed the gradual emergence of a reactionary right willing to defect systematically from the existing economic and racial compact. Strategically, the right became focused on using the instruments of minority rule in the existing constitutional order to project power, regardless of whether it represented a popular majority.

The Cleveland Review of Books this year had published plenty of bangers and had several great issue launches. They had two essays that really stood out to me. The first, by Cobi Powell, was his review of the new Thomas Pynchon book, Shadow Ticket. Powell was even handed about a Pynchon book on which the consensus seems to be that it is just alright. Though expecting Pynchon the elder to reach the heights of Gravity’s Rainbow or V. is perhaps to expect too much. However, Powell has the best analysis of the politics of the book I’ve seen so far, making his piece well worth the read.

The second stunner CRB published this year must be Peter Huhne’s essay on Henry James. Looking at the new Peter Brooks book on James as well as NYRB classics’ publication of his essays, Huhne makes good on an incisive insight. The prefaces and forwards James wrote to his own novels are their own little masterpieces of writing, where James lays out his most profound ideas (the term ‘house of fiction’ comes from the start of A Portrait of a Lady!), and yet our most serious collection of James’ writings on literature contains none of these? Assembled by a deep and serious scholar of James these essay were not, protests Peter! The style is wonderful, the point deep and profound. The best writing does not always appear in the obvious places. Give frontmatter a chance!

Joseph Albernaz, if he was from Boston, would be described by his friends as ‘wicked smart’. He’s not from Boston, however. In fact I have no idea where he’s from. He teaches Comparative Literature at Columbia and has a cool book on romanticism called Common Measures. He wrote a pretty damning review of the latest Charles Taylor book not that long ago. But this year his essay on poet Sean Bonney, time and revolution appeared at Alienocene, which is a journal started by people who definitely take too many psychedelics. Albernaz uses Bonney’s poetry as jumping off point to explored how time, the history of the calendar, revolution and death all fit together and fall apart. Albernaz’s essay bears the strange title “Notes on Cleft Calendrics”, but it is well worth your time (ha).

There was a lot of bullshit this year. My favourite piece of bullshit this year was when Sam Kriss just straight made up a guy called Lord Humungus, a figure of terrifying strength and brutality that rides across England searching for fuel for his war bikes. He appears in a genuinely serious piece about the absurdity of the UK’s declaration that the group Palestinian Action is a terrorist organisation and the limits of the law, whose excellent points are not diminished by the entirely fictional story of Lord Humungus.

Australian scholar Gregory Marks loves Hegel. I can’t really hold that against him, although I hold it against almost everyone else. That’s because Marks is great writer and a deeply insightful young intellectual. His essay on Gillian Rose’s Love’s Work and the tale of Sir Gaiwan and the Green Knight is a really wonderful piece of writing. The essay, entitled “The Law of Shame” pulls out the threads of comedy and humiliation that lie within Arthurian legend. Not so much against Rose but in supplement to her, Marks offers the tale of Sir Gaiwan and the Green Knight, a story the ends not so much with Sir Gaiwan’s tragic defeat but his humorous humiliation. Rose’s analysis of Arthurian legend is meant to emphasize the tragedy of law and right: when Guenevere and Lancelot’s infidelity is discovered Sir Arthur can either forgive them and fail as a king, or follow the law which calls for their execution and fail them as friends. Rose cautions us: whatever the king does, he must be sad. Yet for Marks Sir Gaiwan and the Green Knight tells us a different story about what binds us together, pulled from the very same mythos:

Seeing his shame, the other knights laugh, not in mockery but in recognition of their own folly. Every one of them is bound by duties the source of which they do not know and with ends they cannot realise. The virtue that emerges in this broken middle between knowing the good and recognising that we err is humility, the human passion of which is shame. Whereas the tragic hero is perfected in death and the realisation of their fate, Gawain is perfected in life and the recognition of his shame, by which this erring “I” confesses and is absolved in the “I that is We and the We that is I” of the self-conscious collective. In memory of this lesson, the knights take the green sash as their emblem; a reminder against the follies of reason’s perfect laws and of their common humiliation.

Mathis Fuelling’s essay in Negation Magazine on Kohei Saito and degrowth communism was really excellent. In the end Fuelling makes a really simple but important point: so much of degrowth communism and ecological Marxism more broadly has us shifting through notebooks and the one hundred and fifteenth volume of the Gesamtausagbe to find the one place Marx made a remark about the soil. Of course, Marx is sensitive to ecological concerns, but this tendency towards Marxology as redemption tires Fuelling as much, it appears, as it tires me.

I wrote a missive this year for A Common Well Journal, but so did its editor Hank K. Jost. He’s not inclined towards the essay, Hank is 100% a fiction guy. Yet this essay, but how much he hates writing essays is rather spectacular, and ends with a 1,000 word sentence.

Amia Srinivasan just published, like it really just came out, an essay on psychoanalysis over at the LRB. She looks carefully at the intersection between psychoanalysis and politics. Psychoanalysis, historically, emerges as a turn away from politics: Freud’s project begins in earnest only once reactionary forces come back into power in Vienna. Srinivasan’s breadth of references is impressive, and she takes as her starting point the obvious genocide in Gaza as well as the appearance of Parapraxis magazine, the leading edge of psychoanalytic prose. Indeed she opens with a quote from Jake Romm from one his 2024 essay in Parapraxis, Elements of Antisemitism. Romm wrote another favourite essay of mine this year. His essay Against the Wound (LARB) charts a short but poignant excursion through atrocity, art history and the meaning of death. Both Srinivasan and Romm have Gaza in mind as the impetus of their writing. Yet both pieces represent a decisive shift in writing about Gaza. I have been reading less about these events, partly due to my own choices, partly due to the algorithm. Yet I cannot help but feel that we are also settling into the world where this has happened. Previous essays has a sense of urgency, a mood dominant by shock. Both Srinivasan and Romm are more reflective, though Romm’s anger is palable as always. Both are asking ‘what now, what next’, whether they realise it or not. It is not surprising that both end thier pieces looking forward. Srinivasan closes her essay by suggesting a somewhat forced link between organising and the talking cure, closing with a sense of here’s how we can get from psychoanalysis back to politics. Romm ends his essay with a strange scene where he finds himself in a museum during a school trip, ducking and weaving between hordes for children, potent symbols of the future, indifferent to the art as he returns to gaze at Luca Giordano’s Saint Michael, the painting he has spent the last 3,000 or so words telling us about. There is no rallying cry or powerful closing remarks from Romm, just simple dissipation. A vision of the future, however ambiguous, as the year draws to a close.

Finally some Coetzee love!