The unexamined life is not worthing living, famously declares Socrates. Yet philosophy, the discipline that supposedly begins in wonder actually begins in aporia. Aporia is the Greek word for something which cannot be passed through or overcome, the ‘a’ indicating a negative, poria a passing. Therefore aporia, something that cannot be passed through, a blockage (often intellectual). The Socratic dialogues feature a lot of banging of heads against the walls of ideas, a lot of circling the drain of the fundamental problems of metaphysics. Characters come and go, but not, as one might suspect, after the resolution of a quandary but after the introduction of a dilemma. The dialogue for which this is the least true is The Republic, and even then Thrasymachus, who believes justice is the providence of the stronger is mocked but leaves before he is properly refuted (at least according to some).

In the Gorgias, then, we should not be surprised to find that examined life is not so worth living either. In a pivotal discussion Socrates and his interlocutors suggest that being a philosopher might incur a certain amount of angst and suffering. Only a truly noble soul who would abandon all pleasure would become a philosopher suggests Socrates. The irony is intentional, your laughter here should be bitter. Indeed this irony is also present in The Republic, when the demands on the silver and gold class who should govern the city become increasingly excessive; just what, exactly, are the conditions of the just city?

Given this, perhaps it is better to be a poet? Afterall the opposition between the poet and the philosopher is a Platonic one and remains with us in our crass opposition between intellect and intuition, form and feeling. The poet, Socrates eagerly tells his interlocuter Glaucon, works at three removes from the truth and does not exercise any skilled practice. We do not go to Homer for medical advice, and he has not navigated his way to victory in any great battles. Witness then the erection of the division between the idea and the poem: “all poets downward from Homer have no grasp of truth.”

Paul Valéry, one of history’s great poets, belongs to a lineage of poets for whom the gap between the idea and the poem was to be collapsed. Yet it does not take long for Valéry to find the life of the poet tedious: in 1892, he gazes upon a storm of terrific malevolence and gives up on poetry. What does he turn to instead? Philosophy, of sorts. In lieu of his poetic efforts he begins to work on new character, one of a certain Cartesian excellence, who will embody the finest intellectual spirit of not only his age but all ages. Hence the creation of Monsieur Teste, Mr. Head if you want, though, as Ryan Ruby is keen to point out in his introduction to the new NYRB edition of Monsieur Teste, the French is slightly more subtle, with connections and connotations to both the words testify and testicle. A windbag and ballbag both, Valéry’s literary and philosophical creation is Frankenstein in fragments and letters. Yet how far did Valéry really travel from his own poetry to the world of ideas? His belated return to poetry suggests that the world of ideas ultimately offered Valéry little comfort. Yet his poetry itself was already worthy of the cerebral heights of Monsieur Teste. The life of the poet and the life of the philosopher have collapsed in the poem of the idea, which heralds a new idea of poetry itself.

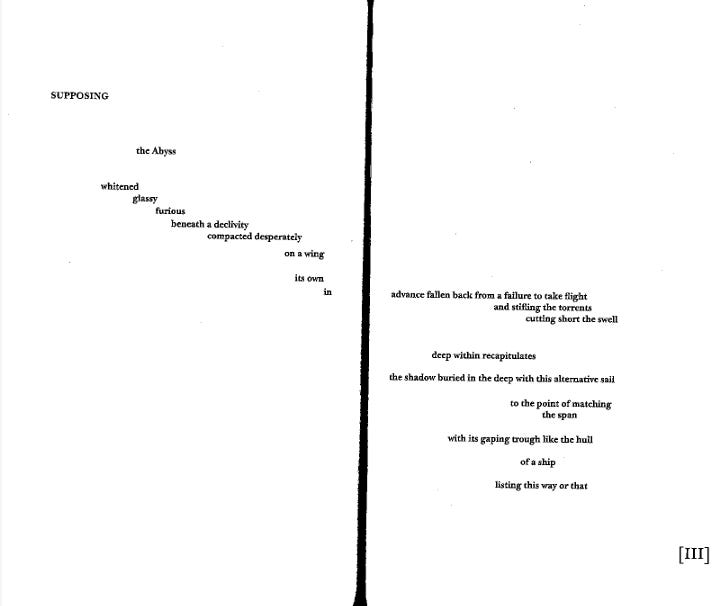

Valéry’s poems, before he stopped writing them, reflected a certain abstractness, one codified and associated with Stephan Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud. A Symbolist, Mallarmé’s poems were both finely tuned and associative, deeply abstract but not in the goal of achieving any immediate meaning. They were heavy on image – including the image formed on the page by the poem itself – and less interested in the pure evocation of feeling. More precisely: the sought to evoke the feelings associated with the lofty highs of abstraction, the pleasure of the furrowed brow. This reaches its apotheosis in Mallarmé’s most famous poem, ‘the throw of the dice will never abolish chance.’ It is better to show you a snippet of it then to explain it:

What are these lines written out? “The Abyss/Whitened/Glassy/Furious/Beneath a declivity/compacted desperately/ on a wing/ it own/in advance fallen back from a failure to take flight.” What meaning presents itself to us here, what classic form bounds these words? The emphasis on shape, on geometry, feels as inseparable from the poem as the words, and indeed is one of the main aesthetics features of ‘the throw of the dice’. One feels here Mallarmé mocking Plato: poems are all appearance, alright!

The throw of the dice is Mallarmé pushing the boundary to the extreme. But in a poem less formally (by which I mean visually) inventive – such as Hérodiade - the idea still reigns supreme:

Abolished, and her frightful wing in the tears

Of the basin, abolished, that mirrors forth our fears,

The naked golds lashing the crimson space,

An Aurora—heraldic plumage—has chosen to embrace

Our cinerary tower of sacrifice,

Heavy tomb that a songbird has fled, lone caprice

You can certainly analyse this poem on the grounds of its imagery, but what will strike a reader immediately, even in translation, is the emphasis on rhythm and sound above sense making. This is poetry for poetry’s sake, a whole half a century before Getrude Stein’s infamous “A rose is a rose is a rose.”

Valéry’s poems followed in Mallarmé’s footsteps. Indeed, his notebooks record his idea that poetry is more about its “program” than any given subject. Poetry is not about things, it does things. Read those lines of Hérodiade again and tell me what exactly is being portrayed and why. What exactly does it mean to “mirror forth our fears.” I am not suggesting such questions cannot be answered; however I am suggesting that it is not obvious. What is obvious is the poetic and rhythmic value of “forth our fears”, which is both alliterative and assonant.

The point is not that symbolist poems resist interpretation, that they could not possibly be understood. It is rather than these are poems that have turned sharply and decisively from being about things to being about poetry. The hermeticism is self-referential. Rimbaud, who also belongs to this moment in poetry famously declares “method, we affirm you!”, a decisive declaration of intent.

Valéry did not always reach for the formal experimentalism of Mallarmé, but he maintained a certain poetic density and committed himself rigorously to form and technique. This perhaps seen in Valéry’s tendency to maintain a single image throughout his poems, developing formal variations on single theme. The length of his poem ‘Young Fate’ sits in direct opposition to the dominant image of the poem. For the poem has a speaker and concept well defined: a young man, overcome with emotions he cannot quell. And from this Valéry spins pages and pages of carefully formulated poetry. As with Mallarmé, the point is made best by seeing the poem’s shape before one reads it. The following occurs on the third page of this twenty-page poem.

This is not a poem that is meant to (only) convey its image, this is a poem that is meant to see for how far and how long one can spin out an image, while adjusting rhythms and structures and symbols. The idea of poetry, its form, comes before its functions. Although ‘The Young Fate’ is a poem Valéry published in 1917 after his hiatus from poetry and the written word, this approach is there, embryonically, in early poems like Narcissus Speaks and The Spinner, which begin this process of weaving a single malleable topic through the techniques of poetry. The function of poetry is to make poetry, not to convey (emotions, images, thoughts, take your pick).

The new idea of the poem as the poetry of ideas soon exhausts a young Valéry. If ideas are what counts, why not tackle them head on? Better, perhaps, to be a poet? Not so. In 1892 while in Genoa, Italy – the same place where Gustave Flaubert is inspired in 1845 to write the first aborted version of The Temptation of St. Anthony – Paul Valéry decided to abandoned poetry. The cause of this is commonly understood to be a particularly intense thunderstorm that result in belief that poem was not the proper vehicle for the idea. Valéry would not return to poetry till 1912. In the meantime, he focused on his notebooks and other writings, including his creation of the strange Monsieur Teste. I have already suggested above that this leads itself to a reading wherein Valéry chooses the life of the mind over the life of the poet. A short online biography and introduction of Valéry goes so far as to suggest that “the fictional character of Edouard Teste…[was]…a paragon of intellectual austerity and self-absorption, an “ideal” thinker, and therefore a role model for Valéry himself.” Indeed, when Valéry gave up poetry he dedicated himself to his notebook, to his Monsieur Teste, and to pseudo-scholarly works on dreams and Da Vinci. In other words, he turned from poetics to speculation.

At first it seems as if Monsieur Teste is to be envied. He is not only wise and smart, but his wife and friends and fans and even the state all think so well of him. We are treated to a letter address to Monsieur Teste which, as we read, begins to seem tedious in its praise. His wife’s – Madam Teste, of course – reflections on him strike one as less loving and more infatuated. The state assembled report which closes the volume takes the tone of bureaucratic objectivity, a while pronouncing Monsieur Teste a genius, finds him troubled and lonesome.

Monsieur Teste, it slowly turns out, is no celebration of the life of the mind and the philosopher. Rather it is an account of the pain and the blockages of the idea. For example, consider this passage:

Until quite late in life, Monsieur Teste was not at all aware of the singularity of his mind. He thought everyone else was like him. But he thought he was dimmer and more stupid than most. This observation led me to note his weaknesses, sometimes his accomplishments. He noted that he was quite often smarter than the smartest and duller than the dullest – a very grave observation that can lead to a policy of abuse and unevenly distributed concessions.

Certainly, Valéry is describing an enviable genius here, but he is also describing a man who is cursed, whose own intellect prevents him from being fully human. In a piece imaginatively called “The End of Monsieur Teste”, Valéry terminates his creation with all the bitterness that has been boiling under the surface:

Syllogisms impaired by agony, thousands of joyful images bathed in pain, fear mingled with lovely moments from the past. What a temptation, though, death is. An unimaginable thing, which gets into the mind as desire and horror by turn. End of intellect. Funeral march of thought.

Better perhaps to be a philosopher than a poet? Not so. Monsieur Teste, exhausted, more than just a mere mind (“impaired by agony”, “bathed in pain”), imagines the end of all thought. And there is some sense of relief here. Perhaps the life of the mind has been too much. It is hard to read all of Valéry’s Monsieur Teste’s fragments and imagine a man for whom life has been a pleasure.

After 1912, when Valéry returned to writing, he seems to have accepted that his distinction between poetry and the philosopher is limited. Things are a little more complicated. In his 1939 talk “Poetry and Abstract Thought”, the philosopher and the poet are reunified: “If the logician could never be other than a logician, he would not, and could not be, a logician; and if the poet were never anything but a poet without the slightest hope of being able to reason abstractly, he would leave no poetic traces behind him.”

While the statement seems obvious (although it may not have been obvious for Plato and Socrates and dear Glaucon), it signifies for Valéry a distance travelled. The triumph of the post-1912 poems, including Young Fate cited above, take this reunification seriously. The poem and the idea in conjunction, not disjunction. Something else, too, has shifted. From the sour ending of Monsieur Teste Valéry’s poetry will now, on occasion, express a different outlook. This perhaps seen best in the closing stanza to Valéry’s most famous poem, the 1920 Graveyard by the Sea:

The wind is rising!..We must try to Live!

The immense air opens and shuts my book,

A wave dare burst in powder over the rocks.

Pages, whirl away in a dazzling riot!

And break, waves, rejoicing, break that quiet

Roof where foraging sails dipped their beaks!

End of intellect. With which, however, the procession of thought begins.